16 May How To Capture A Wild Giraffe

The giraffe was officially declared as a critically endangered species in Kenya in 2018.

But the problem isn’t only in Kenya. It continues all over the African continent, where giraffe numbers have fallen so sharply over the past twenty years that it is being referred to as a “silent extinction” of the species. Where there were once 140,000 giraffes only a short time ago, there are now fewer than 80,000, and that number is continuing to fall.

There are two key factors driving the demise of this magnificent and irreplaceable species. The first of which is habitat loss or fragmentation which, in Africa, is occurring due to the increasing amount of land being used for agriculture. When this land use encroaches on wildlife corridors – the natural migratory paths of a species – it leads to the fragmentation and disturbance the cyclical movements of that species. This can, and does, lead to increased pressure from predators, interruption of reproductive cycles and, critically, a lack of access to appropriate food or water during certain seasons.

The second factor contributing to the decline in giraffe numbers is poaching. This is of particular concern in East and Central Africa where it is rampant. Giraffes are poached for their meat, skin and even tails, the latter being used as a symbol of authority in many African nations. Their bones are in high demand in Tanzania where there is a widely-held belief that the marrow can cure those suffering from HIV-AIDS and despite government restrictions on hunting, including a total ban in national parks, they also continue to be poached as trophies.

Sadly, those who poach for trophies are often wealthy foreign tourists who pay willing or desperate locals to take them hunting. This illegal activity occurs across a wide range of species on a daily basis, but occasionally comes into the spotlight with cases like Cecil the Lion who, in 2015, was infamously slaughtered in a protected area of Zimbabwe by a paying American tourist.

And now, with the lifting of the import ban on certain trophy items by the USA in 2018, the demand has only been fuelled. And, to further worsen matters, there remains a false but generalised belief that giraffe numbers are stable, which has resulted in many giraffe species being omitted from NGO conservation projects.

And that’s where wildlife veterinarians come into the story.

Wildlife vets in Africa

Much of the work of wildlife veterinarians, particularly those who live and work in Africa, involve the movement, or translocation, of an animal or group of animals.

Today, as we know from above, this has become necessary due to several human-driven factors such as poaching and habitat loss. A classic example is the rhino, which is under such severe threat from poaching for its horn, that there are now teams of people working full-time to protect individual rhinos. Additionally, entire herds of rhino are being driven or even flown between African countries in a bid to stay ahead of the poachers.

Elephants are another good example. Poached so severely for their tusks, which fetch up to $100,000 each on the black market, they too often have to be moved to ensure their safety. On the other hand, they are also known to many locals as a pest, frequently trampling fences and destroying properties. So, naturally, an elephant may also need to be translocated for practical purposes (and often does)!

Rhinos may be translocated short distances by air, whereas elephants are translocated in trucks (for obvious reasons!). Image on the left from Dr Pete Morkel.

With every different species comes a different challenge, but none more so than the giraffe. I have been fortunate enough to participate in several giraffe captures across both Zimbabwe and South Africa, yet still always feel as if I’m moonlighting as a stuntman rather than working as a vet! (Questionable decision for someone with my level of coordination…)

Catching the giraffe

Catching a giraffe in the wild is exactly as difficult as it sounds: extremely.

In the space of a few minutes, a highly-skilled team of people have to locate the animal (which is usually moving as part of a herd), get it to the ground, apply ropes and blindfolds, get it back off the ground, and then finally encourage it to walk into a truck.

To accurately describe such a thing is near impossible, but I’ll give it a go!

Darting practice: we painted a target on the back of a truck and it would tear off into the bush so the pilot could chase. It was great to simulate darting conditions in a real capture as opposed to darting in a controlled space, plus the winner would always get a bottle of wine!

To start, the captures are typically performed in the early morning when the heat of the day is unlikely to compromise the animal. The team is split in half – a “ground team” tasked with catching the animal, and a “helicopter team” which is responsible for locating and darting it. (In certain environments it’s also possible to dart from the ground, but it’s much more exciting from the air!)

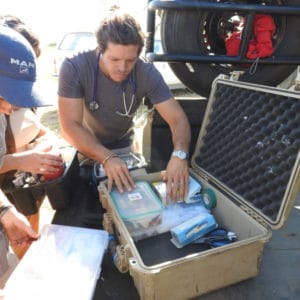

Before beginning, both teams meet in the scrub to prepare the equipment, usually not far from where trackers have last located the animal. The helicopter team takes the dart guns, sedatives and antidote with them onboard. The drugs are often not loaded into the syringes until they are in the air and the animal has been sighted, since its weight and condition are important for dosing. Doing this in a helicopter is a task in itself when considering that the drugs they are handling are 1,000 times more powerful than morphine. In fact, one drop of this particular drug on human skin is capable of stopping your heart in a matter of minutes. For this reason, the darters must always carry the antidote with them and be prepared to administer it to themselves should they need to.

In these captures I was always part of the ground team, and while I was happy not to be darting a wild and galloping giraffe from the door of a low-flying helicopter, there were usually some equally-sizeable challenges to deal with on our end! Instead of darting the giraffe, our task was instead to bring the half-sedated, galloping giraffe to the ground in a gentle and safe manner. The plan was usually to do this with just two pieces of rope, using a manoeuvre not too dissimilar from a dance I was made to learn in school called the Maypole. (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, lucky you. If you do, who knew it would have ever come in handy!?)

Incredibly, this modified-Maypole manoeuvre involves a lot of weaving in and out of the giraffes’ legs while it is running. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is something that no amount of practice can prepare someone for. However, I suspect that it’s still better than no practice, and because of this we always made sure to do one last run-though before setting off!

Preparing the equipment and setting off

And we’re off!

The following is an excerpt (with photos!) from one of the first giraffe captures in which I was involved, back in 2016 in Zimbabwe.

As the helicopter took off, the rest of us loaded ourselves onto the trays of the trucks, held on tightly to whatever we could find, and sped off into the scrub. In such dense and bumpy terrain, well away from any semblance of a road, we relied entirely on the directions being radioed through from the team above. Over the following minutes it was our job to keep close enough to the action so that we could swoop in quickly once the animal had been darted, but far enough away so as not to interfere with the actual darting process.

After locating the animal, the next move for the aerial team was to try to herd it towards a more open area of scrub where those of us on the ground would have a bit more room to work (read: catch it without having to sprint over, around or under too many bushes in the process). Getting it into a clearing also significantly increased their chances of darting the animal successfully on the first go!

On the ground, the next minutes are a chaotic blur of racing through the scrub in our vehicles, keeping an eye on the helicopters from our position, and deciphering the broken directions coming in thick-and-fast over the radio from the aerial team above.

Then, once we receive word that the animal has been successfully darted, it was time to go!

It was now our role to get to the animal as quickly as possible. Giraffe, as a prey species, are prone to over-exertion when stressed, resulting in the animal potentially running itself to death if the wrong dose of sedative is used. To avoid this, giraffe capture is unique in the fact that a deliberate overdose is given to the animal in order to bring it to ground quickly. The downside to this is that it gives us a very tight window to get there to break its fall, and the animal is at risk of serious physical if we do not make it in time. It is also important to be there to reverse the effect of the drug as quickly as possible, as such a large overdose can cause serious harm if left untreated.

It is at this stage of the capture that anyone not holding onto the truck tightly enough is likely to end up thrown overboard into the scrub. The driver, under pressure to get us to the animal and keep up with directions booming through the radio, swerves sharply left and right, continuously trying to avoid obstacles as they come.

With close to zero visibility as we raced through the thick terrain, our giraffe suddenly appeared in a clearing ahead. The driver of our truck accelerated towards it as we began the chase, reaching up to 70km/hr while dodging rocks, bushes, and other animals to get ahead of it as it thundered down the open plain.

He skilfully manoeuvred us into a position just meters ahead of the animal as it stumbled erratically and gave the call for us to dive out of the vehicle and run. As fast as I could, I dashed to the other side of the clearing, rope flying out behind me as my colleague held on tightly to the other end. We braced ourselves for impact on either side of the rope as the giraffe continued towards us, waiting and hoping that it would not change direction in the last moments.

With a heavily-sedated, wild, adult giraffe barrelling towards us at 60km/hr, I quickly realised that no amount of practice rope-work could have prepared me for this. Fortunately, I didn’t have much time to ponder that thought before the giraffe made contact. It effortlessly pulled us along in its wake until we managed to break its forward momentum – coming to a screeching halt several hair-raising seconds later in the middle of the clearing.

With the now-stationary giraffe swaying meters above our heads, we quickly ran in and out of its thrashing legs with the ropes, doing our best to replicate our perfectly-choreographed steps in these less-than-perfect conditions. Our aim was to quickly, yet carefully, entangle the animal and bring its entire 6-meter body to the ground as safely as possible for everyone involved. In this moment, it’s important to not only be aware of exactly where the animal (and all-four of its very long limbs) is in relation to you, but also to keep your escape route in mind! Perhaps it’s not until you are standing at the foot of a giraffe that you realise just how much distance you need to clear if it decides to come down on top of you!

The darted giraffe is intercepted by the ground team who use ropes to break its fall once the anaesthesia starts to takes effect. Note: these images are from later in the capture, once the blindfold and earplugs had been placed.

So, how do you keep an (awake) adult giraffe on the ground!?

As soon as the giraffe is on the ground, the first thing to do is to administer the antidote. This is injected into the large jugular vein running up the side of the neck, reversing all sedation in a matter of seconds.

And, from here – perhaps rather surprisingly – it’s easy to restrain a fully-grown adult giraffe with just a few people sitting on its neck!

Without wasting any time, four of us scrambled onto the neck which was sprawled along the ground, providing just enough weight to remove the animals’ leveraging power and stop it from getting back to its feet. Being up at the head, I was able to quickly blindfold the animal and stuff giant earplug into its ears – removing any stimulus that could startle or arouse it.

Restraining a non-sedated giraffe is possible with just a few people sitting on the neck. At this stage, earplugs and a blindfold are placed to remove any stimulus and the animal remains quite calm throughout.

Surprisingly, once the ear plugs and eye-mask have been applied, even wild giraffe become quite amenable to handling.

It is at this stage that any treatments can be done – from blood sampling, treating wounds (such as snare wounds) and removing our dart. This last step is done carefully so as not to splash anyone with any drug residue, and the site is cleaned and highlighted with spray-paint for extra caution.

As everything is happening around us, for those of us on the neck, our main priority is staying there. From where I was, I could feel the animal gently attempting to rise – my knees briefly leaving the ground each time. It reminded me of an anecdote I’d been told from many years before about another vet who had been in my position on the neck of a giraffe. Unfortunately for him, however, his team no longer was! Without the added weight, the giraffe got to its feet and galloped off into the scrub – taking him along for the ride! The only thing left to do, he later told me, was to close his eyes, let go of the neck and curl up into a ball – hoping that one of the enormous legs wouldn’t get him on the way down. It’s a story that I will never forget, and one that was certainly in the forefront of my mind on this particular day!

On the road again

As you can see, it’s even possible to walk a blindfolded giraffe – minus a bit of kicking in the first few steps as it gets accustomed to the ropes!

This is, in fact, the primary way of moving any giraffe in the wild. They may be walked (non-sedated) to a trailer for transportation, or even directly to their destination if within a certain distance.

For those going into a trailer like ours, you can be guaranteed a few odd looks by passers-by on the motor-ways! Aside from that, it is usually an uneventful journey as giraffes travel remarkably well (but need little encouragement to get out once they arrive)!

In the trailer and ready to go! The giraffe travels well with the earplugs and eye mask – in fact, much better than many of the motorists we passed!

Final thoughts

It is always a privilege for me to participate in this type of work. Although extremely exciting from a veterinary perspective, it’s my hope that it will no longer be necessary to translocate animals for safety purposes in the future. Until that time, wildlife veterinarians will continue to do their jobs to protect them as best they can.

For any budding wildlife veterinarians out there, I have linked to my favourite wildlife medicine textbook below! It includes details on the capture and restraint of many different species, along with the medications and doses used. It also has a lot of anatomy and physiology! The link will take you to your local Amazon shop that sells it. And as always, please don’t hesitate to get in touch if you have any questions for me!

My favourite wildlife medicine textbook for any budding or qualified wildlife veterinarians out there! This link will take you to the textbook in your Amazon store:

Miller – Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine Current Therapy, Volume 9

And if that’s just not enough, check out this great formulary for a range of exotic species:

This post contains affiliate links. Please read my disclosure for more information.

Minda I Centsandfamily

Posted at 13:41h, 29 SeptemberWOW. Thank you for sharing your experience and for giving us a window into what you do! I haven’t seen anything like before.

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 15:25h, 29 SeptemberIt’s my pleasure to share this work, and hopefully give an insight into what wildlife vets do! Thank you for reading!! 🙂

Melissa Jones

Posted at 13:43h, 29 SeptemberAmazing information and amazing pictures!!

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 15:25h, 29 SeptemberThank you!! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

Jenn Summers

Posted at 13:48h, 29 SeptemberOh my goodness! this is absolutely incredible. the work that people like you do amazes me. Thank you so much for your hard work and skills to help protect the giraffes and other endangered species!

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 15:31h, 29 SeptemberThank you so much – it truly takes a village of people to accomplish something like this! I am just happy to be a very small part of it 🙂

Living with mental health

Posted at 14:03h, 29 SeptemberThis was awesome information and thanks for the pictures going to give you a follow.

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 15:32h, 29 SeptemberMy pleasure! Thank you!

Kimberlie

Posted at 14:33h, 29 SeptemberI thoroughly enjoyed your post. I teach units of animal endangerment and am excited to share this “boots on the ground” account of those who are trying to help. Thank you for what you do and for sharing it with others

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 15:34h, 29 SeptemberHi Kimberlie, it is so nice to hear from you – thanks for your message! I’d love to know how you go telling your class about this story, it made my day hearing that you plan on showing them 🙂 Please let me know if I can provide you with any extra photos or information to help!

Faith Oge

Posted at 17:07h, 29 SeptemberNice post. You’re indeed a juncle doctor.

Keep up the good work.

Sharon Green

Posted at 17:14h, 29 SeptemberThanks for a very interesting and informative post! I enjoyed reading about what you do to help endangered animals in the wild!

Patricia Turk

Posted at 17:47h, 29 SeptemberIncredible documentation! I couldn’t begin to imagine the adrenaline that races through everyone during an event like this. WOW!

TheGlobeTrevor

Posted at 04:01h, 30 SeptemberOh wow, that is so cool! Thank you for the work you are doing.

Maybe we can convince some hunters to hunt with dart guns to actually help the animals instead of killing them. As in signing up to do it, not just randomly.

Stephen Russell

Posted at 20:42h, 19 NovemberDo we still capture giraffes like in movie Hatari or have trucks etc been improved since then?