30 Mar Life on Kangaroo Island and Raising Ruby the Roo

In early 2018, Jan and I spent three months working on Australia’s remote and beautiful Kangaroo Island. The island is a largely-untouched natural paradise, home to some of Australia’s rarest and most endangered species, along with some of its most populous. In the latter group, and perhaps unsurprisingly, there’s no shortage of kangaroos. In fact, the island even has its own subspecies known as the Kangaroo Island Kangaroo – one of whom we got to know very well when we unexpectedly became her foster parents!

Life on the island

Our decision to return to the island was easy after falling in love with it and becoming engaged there on a holiday in early 2017. We were drawn to its relaxed way of life, unspoilt natural beauty, abundance of wildlife, and bumpy dirt roads leading to pristine, white sandy beaches with crystal-clear water. It is a place where you can start your morning with a swim with the dolphins, be woken by penguins nesting and chattering under your house (their preferred conversation time is 2 in the morning), watch the whales pass during their winter migration, and be late for work because of an echidna slowly crossing the road in front of your car.

The local brewery is in a paddock where you can recline on hammocks and look out to the ocean, and one of the best eateries in town is inside a magnificent old fig tree. On top of all that, with a population of less than 5000 people that are spread out across the deceptively-large land mass, it is also a place where you can have the entire beach to yourself – usually only sharing it with a group of sun-bathing sea lions who are almost certainly laughing to themselves as they watch you learn to surf.

So yes, for us, the decision to return was not a difficult one. I had been offered a job as a vet in the island’s only veterinary clinic, which tends to all the animals of KI, wildlife included. Jan’s role, on the other hand, was a slightly less conventional one – he would be joining the “Koala Catching Team” for the season (more on this later, although something this humorous/entertaining really deserves its own post).

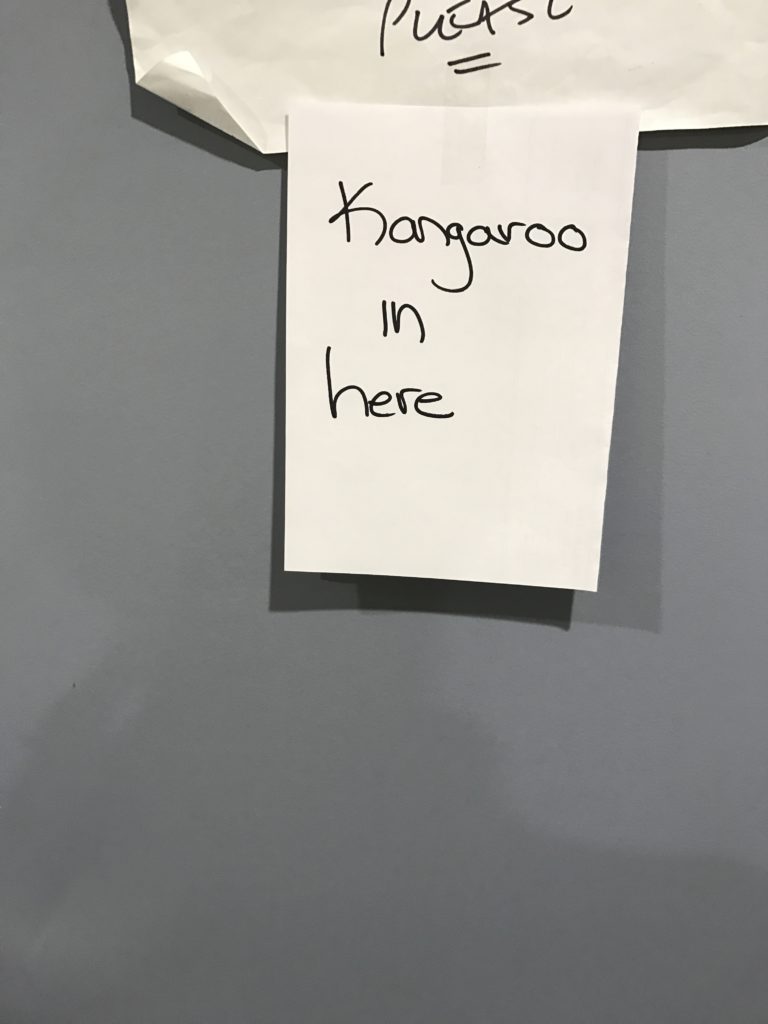

The veterinary clinic itself is small and my days were spent seeing anything and everything from koalas, kangaroos, native birds, and livestock to local pets – most of which were working dogs due to the large agricultural industry on the island. While not too dissimilar in many ways to other remote veterinary practices, we did have a few exceptions, with it not being unusual to arrive at work and be met with a sign like this:

Additionally, without the support of nearby specialist or referral centres that would be available in cities, many complex cases that would not ordinarily be attempted by a general practice required an attempt. On the opposite end of the complexity issue, but again due to our remote location, it also meant that we saw just about… everything. I will never forget the day that a woman presented with a turtle that had a rock stuck up his nose, and the subsequent moment that I realised how completely useless my six years of schooling were because WHERE was my rock-stuck-in-turtle’s-nose lecture!? (Happy to report that the rock was removed – the answer is tweezers)

Koala catching

While I spent my days in the clinic (primarily as a turtle ENT) or out on calls, Jan would be in the bush with the official Koala Catching Team – spotting and gently lassoing female koalas down from trees before bringing them into the clinic for sterilization. (As I write this, I am reminded of what a strange sentence that must be to read, but I can assure you that hearing his stories at the end of each day was far more so…)

He was working as part of a government-directed conservation project that was designed to reduce koala numbers on the island. As for why they were doing this – and without getting into the complexities of the population and species dynamics pertinent to koala management – the long and short of the situation on KI is that koalas are an introduced species, and since introduction their population has exploded. Specifically, in a bid to create a “back-up” population should koalas become extinct on the mainland, 18 koalas were introduced onto the island in 1920, and, in a spectacular backfiring of the plan (which would not be the first in our history of species management in Australia), the koala population grew from 18 individuals to 27,000 – far beyond what the island is capable of supporting. Not only does this cause immense, and potentially irreversible, changes to the island’s environment and ecology, but it also poses a welfare threat to the koala which, as a species, is unable to self-regulate their numbers – easily eating themselves out of house and home without correct management.

While I spent my days in the clinic (primarily as a turtle ENT) or out on calls, Jan would be in the bush with the official Koala Catching Team – spotting and gently lassoing female koalas down from trees and then bringing them into the clinic for sterilization. (As I write this, I am reminded of how strange that sentence must seem, but I can assure you that it was far stranger to hear his stories at the end of each day…)

He was working as part of a government-directed conservation project that was designed to reduce koala numbers on the island. As for why they were doing this – and without getting into the complexities of the population and species dynamics pertinent to koala management – the long and short of the situation on KI is that koalas are an introduced species, and since introduction their population has exploded. Specifically, in 1920, 18 koalas were introduced onto the island with the aim of creating a back-up population should koalas become extinct on the mainland. In a spectacular backfiring of the plan (which would not be the first in our history of species management in Australia), the koala population grew from 18 individuals to 27,000 – far beyond what the island is capable of supporting. Not only does this cause immense, and potentially irreversible, changes to the island’s environment and ecology, but it also poses a welfare threat to the koala which, as a species, is unable to self-regulate its numbers – easily eating themselves out of house and home without correct management.

So, as part of the Koala Catching Team, Jan’s day would start at 8am as he and the others hoped to avoid the heat of the day – which, in summer on the island, can be well into the 40’s (104F +). They would meet at the clinic, lather themselves in sunscreen, put on their protective glasses (never mind the snakes, even the trees in Australia will get you – just look up a yakka plant) and set off into the bush, clambering along dried-up creek beds and bush-bashing through the yakkas to find wild koalas. Once a koala was located and found to be a female without an ear tag, meaning that it had not been previously sterilized, the operation to get it down from the tree would begin.

It is here that I can only do my best in describing such an event to you. But, regardless of what I write, I am almost certain that I could never do justice to such a thing – so, for a little more of an idea, I have attached a YouTube video. This video roughly outlines the process, and definitely hasn’t dated at all since its filming, in what I can only assume was the 1960’s:

As you can see, the whole process is a combination of one or two people scaling an enormous gum tree, waving a large flag above the animal’s head in a bid to get it to move down the tree, and securing a light rope around it to prevent a daring, leaping escape to surrounding trees (yes, I too had underestimated the humble koala…). The rope is also useful in case the koala decides to do a “drop and run”, where they will release their grip from the tree, roll into a ball, bounce upon hitting the ground, and take off at speed into the bushes (another party trick that people didn’t seem to think koalas had up their sleeves).

Then, if you’ve managed all of that and the koala is now at the base of the tree, the “grabber” will swiftly take hold of the animal (avoiding its dagger-like claws) and place it into a thick bag in which it can be transported to the clinic. Finally, the last thing you have to hope for by this stage is that there are no males in sight who may wish to challenge you for that female – with stories of people being chased down trees and speedily across the scrub not being uncommon!

At the end of each day, the koalas were released back to where they were found and Jan would make it home around 6pm, covered in dirt and grinning from ear to ear about his day with them. In a short period of time he had somehow become the most Australianised German on the planet – contending with 40-degree days, snakes and yakka bushes in order to catch some koalas – and being as absurd as it is, I’m quite sure that nobody back home in Germany believes a word of it!

Down time

When Jan was on a break from the koalas and I had a day off, we spent our time learning to surf, finding small camping spots in some of the many different corners of the island, and even dabbling in brewing our own beer. In fact, we took such a shine to brewing that it wasn’t long before we had bought ourselves a little bottling machine, given the beer a name (complete with logo), and designed ourselves some labels!

Then we hit a problem. When it came to printing, the only labels that we had available were those from the clinic pharmacy – and wasn’t long before our beer was known as the KI Vet Clinic Beer (“for animal treatment only”)!

Ruby the roo

Despite how much fun it was to learn to brew beer, listen to Jan’s stories about his near-misses with the koalas and relish in a slower pace of life – the most memorable part of our time on Kangaroo Island was when we became foster parents to Ruby the Roo, an orphaned kangaroo joey. I remember the morning that she arrived at the clinic – she was in a padded carry bag and dropped off by a tourist, having been found alone and disorientated in a paddock. Based on her size and measurements, we aged her at approximately 8 months – meaning that she would have only just started to leave the pouch, and that she was still on her mother’s milk.

A medical examination deemed her to be healthy, but due to her age and the fact that she was still nursing, she would need to be adopted and hand-reared. Sadly, it was likely that Ruby had been orphaned when her mother was killed in a road accident, as is so often the case when people live in such close proximity to wildlife. I didn’t have to think twice about taking her, and when Jan came to pick me up that evening after work, we had a new addition to the family!

As baby kangaroos spend much of their time in the pouch (all of it, in fact, before 8 months of age), their preferred method of transportation is in a pouch – or in our case – a handbag. Ruby came home in the bag, and we assembled a special frame in our room from which we could hang the bag while she slept. We decided that she would be called Ruby the Roo, and got to work figuring out her feeding schedule.

Since she was 8 months old, we took the appropriate milk replacer for her age (the milk changes in composition based on the joey’s age and requirements), calculated what she would need and how often she would need it. Kangaroos do not usually start to wean off milk until at least a year of age, and Ruby’s diet would therefore consist entirely of formula. Once we had worked it out, we found that it came to a total 120mls a day – or 10mls every two hours.

To say that the next few days were a steep learning curve is an understatement. Firstly, I realised that, just like any other baby, kangaroo joeys cry when they are hungry and, just like other babies, they always seem to be hungry. I also learnt that a kangaroo cry sounds like a loud, harsh cough – and can be startling to say the least, especially at 4 in the morning. For the first time, I learnt exactly how total sleep deprivation feels, but, on the other hand, I also learnt just how speedily a person can make a midnight bottle in their sleep.

As for kangaroo joeys, they also taught me several new things. Firstly, I discovered that they always enter the pouch with a forward flip or somersault. As a joey only new to the world outside the pouch, Ruby was unsteady on her feet, and sometimes off-aim with her somersaults. This meant that you had to be quick on yours to make sure that she still landed in her target!

As for which bag to put them in – despite finding the most comfortable and padded one that we possibly could, we learnt that they don’t care at all. Ruby would try to flip into anything that even closely resembled a bag. She was fussy however, on how the bag was hung on the frame, not settling to go to sleep until it had been readjusted. And when it came to feeding, we had an uphill battle on our hands there, with Ruby refusing several different teats until we finally found one that met with her approval.

Despite a few bumps along the road, it was only a few days before she settled in at home with us and began to get out of her pouch more frequently. Jan had quickly become “mum” (I assume because he was far better at the midnight feeds than I was – sorry Jan!), and Ruby followed him most places around the house. We also noticed that all crying had stopped, as had some occasional teeth grinding, which is a known stress response in the species.

Hopping school

As she got steadier on her feet, Jan built her an outdoor enclosure in our backyard where we could go to “hopping school” with her every day.

We would spend an hour or two at a time out there with her, sitting on the grass as she explored her environment, occasionally getting startled by birds and hopping straight back to her pouch. She would become playful and bounce over our laps, and then speed up to one end of the enclosure before overbalancing and taking a tumble. She would chase us around, and when she became tired, she would beeline straight back to the pouch – managing to stay awake just long enough to guzzle down a bottle of milk before passing out for hours on end!

When our stay on the island came to an end, Ruby went to another wildlife carer where she remained until her release several months later. It goes without saying that our three months on the island, and in particular, our one month with Ruby, have left us with some very special memories. We can’t wait to return to this little corner of the world and, if we’re lucky, maybe even cross paths with Ruby in the wild one day!

Emily Adams

Posted at 12:31h, 29 SeptemberWhat a wonderful experience! KI sounds like the perfect place to enjoy nature and wildlife. I had no idea koalas were so tricky and Ruby sounds like a handful. Picturing the somersaults in my mind made me laugh 🙂

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 14:35h, 29 SeptemberThanks so much, Emily! KI is certainly a very special place, and koalas can definitely be a handful! Looking forward to sharing more adventures from there with you soon! 🙂

Kristin H

Posted at 14:00h, 29 SeptemberThat is just the cutest story, thank you for sharing!

Jungle Doctor

Posted at 14:36h, 29 SeptemberMy pleasure! Thank you for reading it! 🙂